A Woman in Berlin by Marta Hillers : Summary & Book Review

Reading this testimony, we think of Ingrid Brunstein's who wrote: "the coexistence of two disasters, one of which was the cause of the other, does not neutralize either of them". A woman in Berlin appears as a forbidden testimony. A stone into the water. In the aftermath of the war and the opening of the camps, Europe discovered horror. Post-traumatic shock. We're ashamed, we want to forget. Germany becomes persona non grata. No wonder then that its first publication in 1957 was a failure. Above all, we do not want to have Germany's opinion.

This book transmits history to us in a way we have never read before. We discover a people abandoned to themselves, forced to abdicate after the arrival of Soviet troops. Bombs, gutted houses, makeshift hospitals, rapes, robberies, bartering, burials. The lack of water, milk, gas, smiles. The lack of everything.

A woman in Berlin is not only a war diary, it is a cry. The cry of a people who want to let the world know they were there and suffered. Certainly differently, but they suffered. And its disaster must not be forgotten either.

"Strange period. We live history live, things that we will later tell and sing. But when you're in it, it's all a burden and anguish. History is heavy to bear."

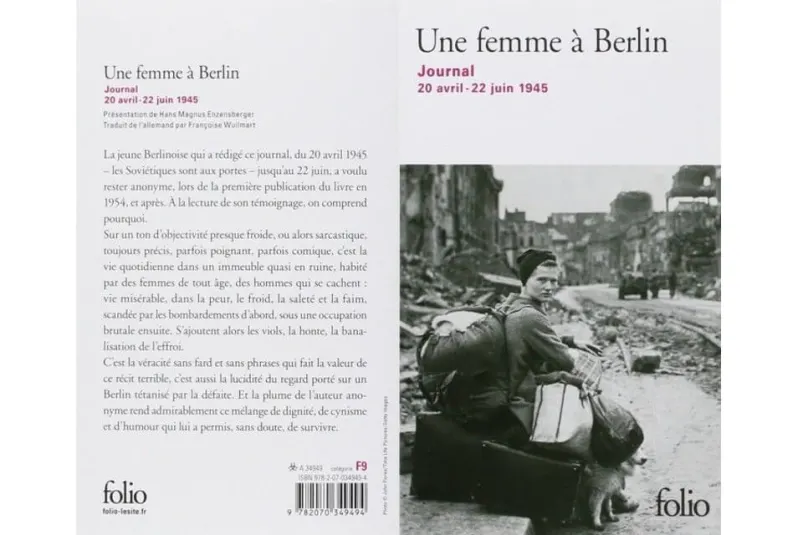

Berlin, summer 1945. The radio no longer transmits, the phone works when it wants. News only comes by word of mouth. We get to know the author, whose identity we will never know. A 30-year-old woman, former employee of a publishing house. She writes her testimony in school notebooks by candlelight or with trembling and cold hands. Whatever happens, writing becomes a duty, a mission. Berlin becomes the front line of this struggle against death and for survival. But what a struggle! Through our author's story, Berlin is getting tougher. She wakes up at 7 a.m., does not hesitate to loot the shops, even if it means cutting her lip after drinking a good bottle of wine from the neck. Berlin is fighting. Then the Red Army. His cows, his tanks, and his soldiers who are taking over the city. Berlin becomes Russian.

In a woman in Berlin, the woman is central. In the Third Reich, she was secondary. She symbolizes the good mother of a family, the hot meal at home, the education of children. At no time does this woman give her opinion on the country's politics. Eva Braun leads a peaceful life in Berghof, far from the chaos of Berlin. Magda Goebbels poses as the greatest mother of the Reich, and portrays Germany as the mother country. In the Nazi system, the reduction of the female gender is done consciously and effectively.

However, in Berlin in 1945, the mother country abandoned its children. The father became Russian and was called Andrei, Aleksei, Iacha, Petka. The youngest women hide to preserve their virginity. Sexual slavery becomes a bargaining chip. Women are soiled and the power is silent. The most terrifying thing is not the coldness with which the author records events, it is the cruelty of history that makes the story icy. And finally, through the enemy's appropriation of Berliner women, we are witnessing the abandonment of an entire people to their political power. To disillusionment.

"I feel completely depressed. We have been stripped of our rights, we have become prey, shit. Our rage is pouring down on Adolf." [...] Criminals and adventurers have become our leaders and we have followed them like sheep to the slaughterhouse."

Then suddenly the sun comes up. A bike ride. Berlin surrenders. The reconstruction begins. We wash the sheets, clean the floors, heal the wounds. We mourn the dead. We're looking for forgiveness. His, theirs. When did this reconstruction end? Perhaps in 2003 during the second edition of the book in a Germany that forgave itself. Anonymous, the author is no longer really so. It was an editor of the daily newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, Jens BIsky, who revealed the identity of the young Berliner: her name was Marta Hillers, she was thirty years old and a journalist.

Laura Darmon

Writer

Passionate about literature, Laura regularly contributes to Berlin Poche. After graduating in law, she has been working in a publishing house as a legal transferee.