How Kreuzberg became the main district of the new Berlin

Berlin's Kreuzberg remains stubbornly true to itself. It is home to digital nomads, street artists and people who prefer analog photography to digital cameras.

Berlin's hipsters: how the Kreuzberg district is changing

Socially and geographically speaking, Kreuzberg was a marginal district of Berlin for a long time. After the war, it was a poor, isolated part of the western part of the city, surrounded on all sides by the Wall. Industrial districts, cheap housing, Turkish migrants, squatters, anarchists - the district developed unevenly. But that was precisely its strength for the future.

In the 1990s, Kreuzberg became the focus of free-spirited people - artists, musicians, writers, students. The factories stood empty, apartments cost an apple and an egg, illegal clubs sprang up in the cellars. Around the turn of the millennium, the first cafés with filter coffee and ceramic mugs as well as stores selling books and cassettes moved into the district. Today it is part of the “new Berlin” - unofficial, urban, with an ironic attitude towards itself and the rest of the world.

Street art as a code of the city

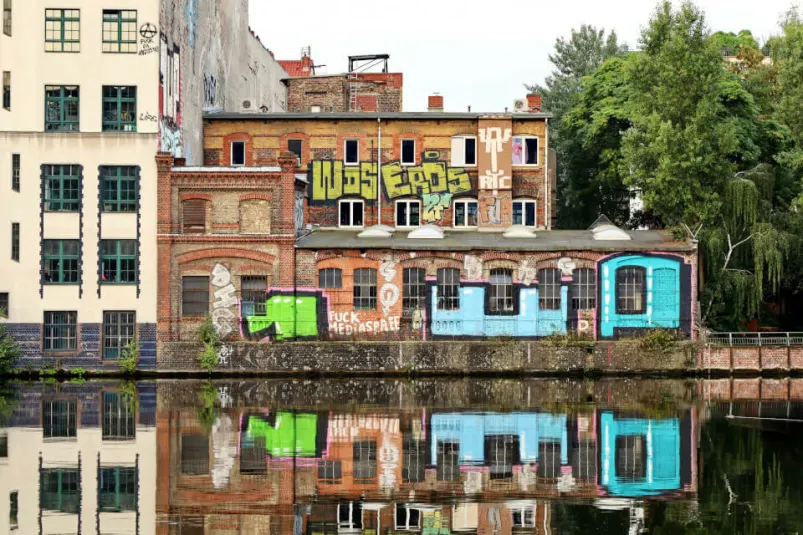

Kreuzberg is a great place to get to know Berlin, but not in the academic sense. There's not a single blank or shiny facade here. Practically every building is decorated with drawings - with casual tags, motivational sketches and multi-storey murals.

The first graffiti appeared in Kreuzberg back in the 70s on trucks, garages and fire escapes. In the 80s, political street art flourished in the area: Slogans against the Wall, drawings of soldiers, distorted faces on white walls. Back then it was the language of marginalized groups, today it is part of Berlin culture.

Today, there are more than 250 pieces of street art in Kreuzberg, which are recorded in the open archives Urban Nation and Street Art Map Berlin. Some works are decades old, such as the famous mural Astronaut Cosmonaut in Mariannenstraße - a project by French artist Victor Ash from 2007 - or the inscription “How long is now” on the façade of the former Tacheles cultural center, which is still printed on T-shirts today.

Stickers, mosaics, QR codes, cut-out silhouettes on traffic lights - all mixed up and on top of each other. The walls are not painted over, but left as they are. The city lets them collect traces.

Doors are photographed in Kreuzberg, not buildings. Tourists specifically drive to the intersection of Skalitzer Strasse and Oranienstrasse to put a new layer over the old one. Even concert posters look like art because part of the wall is already a work of art anyway.

Street art is not only legal in this neighborhood, but is often even commissioned. Restaurants, schools and municipal services work together with artists to integrate the facades into the cityscape. Paradoxically, even banks hire street artists to avoid looking like a foreign body.

The city speaks to passers-by directly on the bricks. Sometimes it is a quote from Kafka, sometimes a sticker with the slogan "Bet small. Think sharp". It can be advertising, a statement or simply an aphorism, but it works. Because in Kreuzberg, even graffiti is organized in its own way.

Who are the modern Berlin hipsters and what do they want?

They don't wear logos and don't take selfies in public toilets. They wear old Acne Studios clothes that they bought at Re-Think or their grandfather's jacket from Münster. Retro glasses, year-round caps, mesh bags with a book about the traumas of post-industrial consciousness.

Their modesty is deliberate, for it is a style made up of irony, second-hand stores and the habit of not throwing anything away. The day passes between a morning latte in a café on chairs from IKEA from 2006 and an evening electro-acoustic concert in an abandoned swimming pool. Instead of series, there are movies, projectors and performances, and instead of a hectic pace, there is free time spread throughout the day.

Redistribution of space - from factories to lofts

Kreuzberg was never homogeneous. There were always strange vacancies between the apartment blocks - warehouses, technical buildings, hangars. Now they are being given a new lease of life. Old industrial areas are being transformed into galleries, workshops, temporary schools and clubs. And all without demolishing the load-bearing structures and without euro renovations.

A typical example is the Aufbauhaus in Prinzenstraße. In the 1950s it was a warehouse for building materials, then it became the offices of the architects' association. Today it houses a bookshop, a café, workshop spaces, a print shop and a stage for performative projects. Another example is the Halle am Berghain. The former East German power station from 1953 now serves as a techno space and exhibition platform. Helmut Newton and NFT projects have already been shown there.

Berlin Poche

Editorial Team

Always looking for new addresses, we like to share our discoveries and make you discover the best places in Berlin.