Nefertiti Bust in Berlin (Neues Museum) - Art & History

The bust of Nefertiti is one of the most famous and beautiful pieces of sculpture in the world. An artwork from ancient Egypt, it is now housed in Berlin’s Neues Museum (we’ll get into that story below). Who was Nefertiti? What was she known for? What did she look like? How was the Nefertiti bust discovered and how did it get to Berlin? Why does it only have one eye? And why did it become so famous?

Let’s take a look at the original, ancient history of the piece, before going on to focus on the modern history.

Who was Nefertiti? What was she known for? What did she look like?

Nefertiti was the wife of Akhenaten, the infamous pharaoh who instated a new monotheistic religion of the sun god, pushing out worship of all other gods and promoting himself as the sun god incarnate. Nefertiti served as his queen from the 1350s-1330s BC (nearly 3.5 thousand years ago!). The royal couple lived in Akhenaten’s new capital city of Amarna, roughly halfway between Cairo and Luxor.

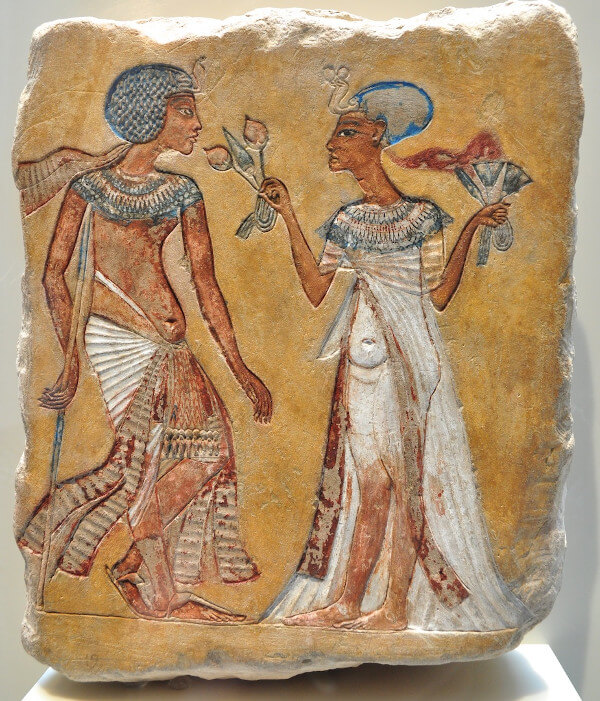

Nefertiti appears in a lot of art alongside Akhenaten, as do their daughters (see photo below). These are not casual pictures of the royal couple: they have a certain point to make. The official message of Akhenaten’s rule is: the Aten or sun disc is the only god, and he is responsible for all life. Symbols of life are big: ankh, but also fertility motifs, like the swarm of children clambering across their parents, or the paunchy belly and wide, child-bearing hips. These are set off by the slender neck and limbs and oversized head, traits that carry through the whole family portraiture – not because anyone actually looked like this, but because these images were meant to promote the ideology. They’re campaign posters! The royal family’s bodies are vehicles for promoting the party line.

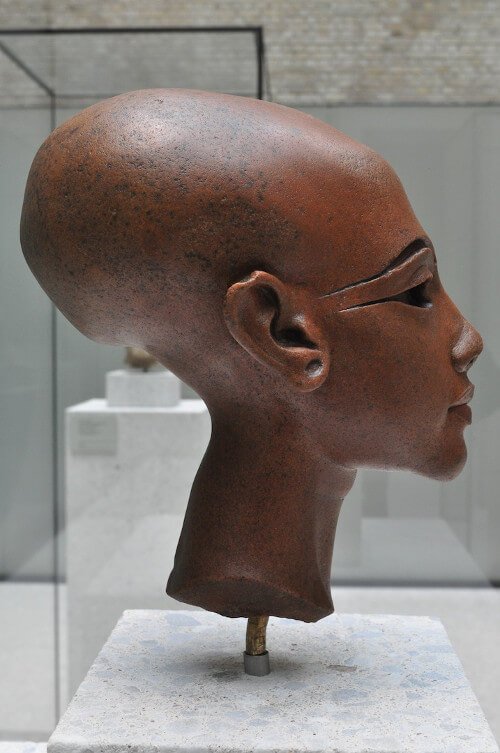

We can see this in the famous bust of Nefertiti as well. The long neck, oversized head – here exaggerated even further by the towering crown she has on, and the forward projection of the neck and chin. These are traits we see in the whole family’s portraiture; here it’s actually nothing unusual. Although the current reputation of this piece is that it is unparalleled – and it is unique in some very important ways – it isn’t unique in its sleek beauty, as we might normally think.

Why and how did the bust of Nefertiti become so famous?

We have to go back to the 19th century: the time of the so-called Big Digs, archaeological excavations on a huge scale. Competition among nations to find great artworks was running rampant!

Germany’s most influential group supporting digs was the German Oriental Society. They were also funding excavations in Babylon that would result in the Ishtar Gate being brought to Berlin. Co-Founder of the society was James Simon, a textile industry magnate in Berlin (for whom the new visitor center on Museum Island, the James-Simon-Galerie, is named). Simon decided to fund an excavation in Egypt, at Akhenaten’s capital, Amarna (then called Akhetaten), with his own personal money and even acquired the excavation permit himself. In return, Simon was granted sole ownership of the German share of the finds. (Back then, finds were often divided between the country where the excavation took place and the country whose archaeologists were working there; this arrangment was called partage, from the French word for “sharing.”)

This was an incredible deal for James Simon, and it would soon become more relevant than anyone anticipated. In the first year of digging at Amarna, 1911, the archaeologist in charge of the dig, Ludwig Borchardt, didn’t find any spectacular objects. But the second year more than made up for it. Borchardt discovered numerous portraits of Akhenaten’s family, a spectacular find.

When and how was the Nefertiti bust found?

In 1912, Borchardt was excavating at Amarna in the ruins of an ancient house. The house had been identified as belonging to a sculptor named Thutmose. (His name and job title were found on an ivory horse blinder found nearby… a standard artist’s studio??). A bust of Amenhotep IV had already been found in Room 19, as well as other interesting fragments. Then… they saw a “flesh-colored neck” in the rubble… The excavators put their tools aside and, using their hands, revealed next the lower part of the bust and then the blue headdress. The portrait of Nefertiti was nearly intact. Borchardt noted that the colors were still so bright, they appeared “freshly painted.” Missing parts of the ear were sought out and discovered; the missing eye was also sought, but never found. Only later, Borchardt wrote, did he realize that this eye had never been set into place; the bust had never been finished. Just like Borchardt’s dig: he never published a full report on it, and couldn’t continue at the site after World War I broke out in 1914.

The bust was taken out of the country in murky circumstances. Borchardt had to share his finds with the local antiquities ministry, but how the discussion of these finds went is unclear. From Borchardt’s own remarks in letters to friends, though, it seems he tried at the very least to benefit from leaving out information: he listed the bust along with other plaster sculptures he wanted to export, hoping that no one would ask what it was, and simply accept the seemingly better stone objects for Egypt. At the personal inspection of his finds, he prayed that the inspectors wouldn’t open the storage box housing the bust. He even wrote that he had chosen a photo of the piece “so that one cannot recognize the full beauty of the bust, although it is sufficient to refute, if necessary, any later talk among third parties about concealment.” (link) He also warned his German patrons not to blabber about the finds until they were safely out of Egypt - because if the Egyptians got wind of the superb artifacts, they might want to keep them.

This does not show Borchardt’s morality in a good light, to put it mildly. Although this was another time, with other customs, it is hard not to look back on it from today’s perspective without qualms.

In 1920 James Simon gave the bust, along with other Amarna finds, to the Berlin museums.

Who owns the bust of Nefertiti? Debates and controversies

The circumstances in which the bust was discovered and taken out of Egypt to Berlin have led to one of the two big current debates surrounding this piece: who owns it really? Not just because of the possibly covert operation, but because Egypt itself at that time was ruled by the British (called the Veiled Protectorate), and the antiquities were administered by the French. So Egypt, and Egyptians themselves, didn’t have a say in what became of their cultural heritage.

Although Egypt has formally asked that the bust be returned to Egypt, the Neues Museum is not reacting. That the Museum celebrated the 100th anniversary of the discovery in 2012 with an exhibition on Amarna is not just a tribute to research, but to ownership.

What is the Nefertiti Bust price?

Its value was estimated a few years ago by an insurance company at 390 million dollars.

The other big current debate about the bust is very modern, centering on new technologies for 3D scanning and printing objects. In 2016, two artists claimed to have made a surreptitious scan of the bust in the Neues Museum and worked it into a very precise digital 3D model. Since then, it has come to light (largely through the work of Cosmo Wenman) that such a scan could not have been made, and the 3D model probably came somehow from the museum itself. Since then, this model has been made public - not by the museum itself, but by Wenman, arguing that “museums should not be repositories of secret knowledge” - so that it can be downloaded and 3D printed by anyone with the resources to do so.

This article was first published on https://museums.love.

Stephanie Pearson

Founder, museums.love

Berlin's Museum Island has been my haunt as a guide, translator, and teacher since 2012. I love bringing visitors the best stories from museums, and doing so in digital media has helped me discover Berlin's cultural landscape from a whole new angle.